Just Where Do Those Flavours Come From?

Malt whisky is generally distilled twice in copper pot stills, but it can be triple distilled or even distilled in a column still, but for the sake of this article, I’m just looking at double distillation. Copper is used to make stills with because of its good heat conducting properties along with its ability to remove some of the unpleasant compounds, such as sulphur in the alcohol. A whisky still can be heated by a direct heat source such as a coal or peat fire, gas, or by steam coils which run inside the base of the still. These stills feature a long progressively tapering neck, generally speaking the longer the neck the lighter and more elegant the spirit becomes because the heavier, oilier congeners (impurities) in the spirit will fall back into the still for re-distillation, this is known in the industry as reflux. Many stills also feature what is known as a ‘boil ball’ at the base of the neck, which increases the copper contact at the ‘sweet point’ in order to increase this reflux and in theory produce a better or cleaner spirit.

At the top of the column is the lyne arm, which can be either angled upwards again, to increase the reflux back into the still, or downwards for no further reflux. This tube finally leads to a piece of equipment called a condenser, which turns the vapour back into a liquid through cooling. There are several different types of condensers in use in the industry, the traditional way to condense the spirit was to use a worm tub, which is essentially a large tank filled with circulating cold water, through which the worm (a copper pipe) runs. Other, more modern types include a Liebig condenser, a shell and tube condenser or a plate heat exchanger. Some distilleries such as Ardbeg, Glenlossie and Strathmill for example will also use a purifier between the lyne arm and the condenser, again, in order to increase the amount of vapour which condenses before reaching the condenser and thus promoting an even greater amount of reflux back into the still.

The first distillation, in the wash still, is essentially a simple process of taking the wort, which is around 6-9% abv and increasing the alcoholic content. As the liquid is heated towards the boiling point of water it produces a vapour which has a concentration of 45% abv. This distillation is continued for around 5-8 hours by which time the alcohol concentration falls to about 1% abv. The resulting product of this first distillation is called low wines, which have an alcoholic strength of around 21-23% abv. At this time the spirit is incredibly far removed from being drinkable as it contains a considerable number of volatile congeners known as fusel oils, which have an aroma akin to sweaty trainers! It also contains quite a lot of the more vegetable like aldehydes as well and having smelt the low wines at Bruichladdich I can confirm that you definitely wouldn’t want to drink them! Sometimes some of the yeast residue sticks to the heater inside the still and as it is baked by the heat it can give a sweet digestive biscuit flavour to the low wines, which will in turn can be found in the finished spirit. These low wines account for around 35% of the volume of liquid, which is in the wash still, the remaining 65% is called pot ale, and being high in protein is often recycled as animal feed. The pot ale has an alcoholic strength of around 0.1% so it’s not going to get your cows drunk!

The low wines are then pumped to a holding tank containing the foreshots (or heads) and feints (or tails) from previous distillations, which typically are around 30% abv, thus combining the two results in a spirit charge of around 25%. The aim of the distiller is to keep the alcoholic strength of the spirit charge as constant as possible. In older distilleries the feints and the low wines are often kept in separate tanks, especially where there are two or three pairs of stills. This means that the composition in the receiver will be constantly changing and if the practice is to pump up to the spirit still charger as soon as the required volume has been collected then the quality and strength of the spirit will vary from one distillation to the next. This is often referred to as an ‘unbalanced distillation’. The best approach is therefore called a ‘balanced distillation’. This is where one or possibly two wash stills feed one spirit still. Only in this system can it be certain that the low wines and feints are truly representative of the distillations because the whole of one or two runs of the wash still goes into one spirit charge, together with the foreshots and feints of a previous distillation.

Now we come to the second distillation, which is where the magic really happens! The second distillation is a fractionated distillation, which means that it is split into three distinctive parts. The first part entails running off the foreshots. As the distillate starts to flow these foreshots contain the most volatile compounds in the spirit – alcohols such as methanol along with acetaldehyde (green apple, metallic notes) and some of the esters, such as ethyl acetate (pear) and ethyl formate (lemon, rum, raspberry). It also contains sulphur compounds such as hydrogen sulphide (rotten eggs), sulphur dioxide (rubber tyres) and dimethyl sulphide (cabbage), which you certainly don’t want in your finished product. The foreshots also have a tendency to ‘clean out the pipes’ of compounds that have separated out of the previously distilled spirit as oils and waxes, which become soluble once again by the high alcoholic strength (around 75% abv) of the initial vapours.

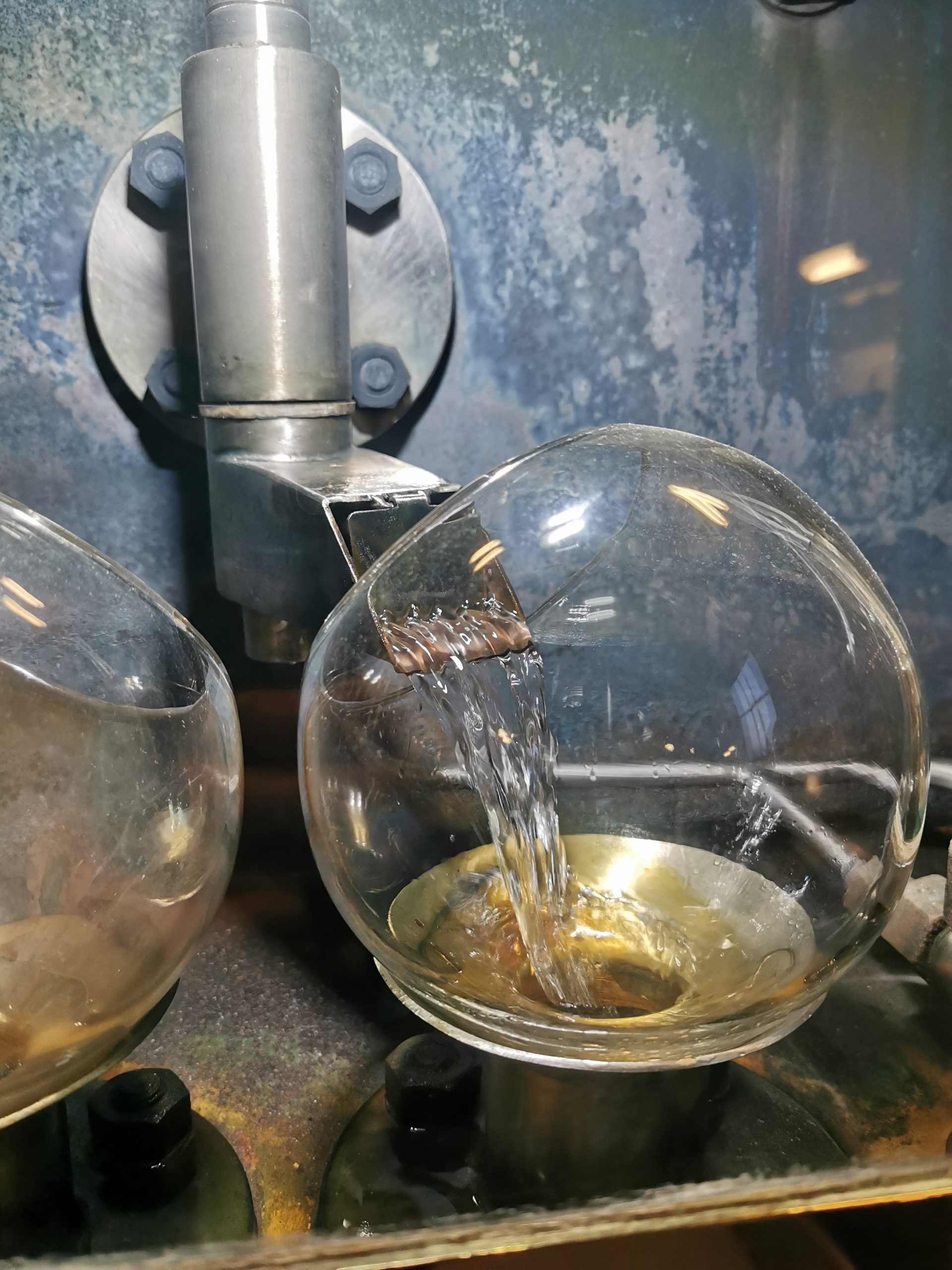

The first cut point is traditionally determined by the distiller by mixing some of the foreshots 50/50 with water in the spirit still. The fusel oils in the spirit are soluble in strong alcohol but by diluting them they drop out of the solution to give a cloudy haze. Only when the sample becomes clear is the distillate judged to be suitable for collection. Some distillers do not use this approach, rather they use a timed foreshots run and are therefore likely to cut the spirit a bit lower as a precaution. As Jim McEwan said to me when I spent some time working at Bruichladdich “The texture of the foreshots is like mutton fat – not very pleasant on the palate or the nose. Then as if by magic, the spirit clears, and the heart is found. Now we are in olfactory paradise. Finding the flavours in the middle cut is like watching rainbows. One minute it’s there the next it’s gone and like the rainbow with its seven colours, there are seven fruit flavours. The fruity esters of pear [ethyl acetate], apple [ethyl isovalerate], banana [ethyl butyrate], peach [linalyl butyrate], apricot [amyl butyrate], melon [isopropyl acetate] and tangerine [octyl acetate] fill the senses. Sometimes there is more pear than tangerine – again each distillery has its own preferred style and if the malt is peated, the aromas are a fantastic mix. It’s like sweet and sour. Add a sprinkle of nutty flavour which will also have come from the fermentation process, and you are in heaven”. Other distillers purely rely on the spirit reaching a certain abv, which can be determined using a hydrometer. So, whichever method is employed the cut is usually taken in the 68 – 75% abv range. The stillman will let the spirit run for between 4 – 6 hours, dependent upon the house style of the distillery. For example, if the distillery style was light and elegant, the distillery would more than likely use a tall still like they use at Bruichladdich and Glenmorangie with a small spirit charge run slowly at a low temperature for maximum reflux and possibly take an earlier or narrow cut. Whereas for a heavier, oilier style a smaller still would be used like at Lagavulin, coupled with a later and possibly wider cut.

The final part of the distillation is the cut from collecting the spirit to running off the feints. The feinty aromas increase slowly towards the ends of the distillation, developing from quite pleasant notes of mushroom, cereal and popcorn through to notes of leather, ash, fish and sometimes cheesy aromas The switch to feints collection is almost entirely done on the basis of alcoholic strength, which is somewhere between 55 – 65% abv. These feints are also rich in phenols and the smoky aromas which are the trademark of many peated whiskies (where those ‘peaty’ flavours comes from is an article in itself, which is why I haven’t gone into any depth about those, but I will in another article!).

Therefore, great care must be taken in determining how much of these potentially dangerous (to the spirit character/ quality) congeners the distiller lets into the final spirit. It is all too easy to take too wide a cut and spoil the spirit with the addition of too much of theses congeners, such as amyl alcohol (a toxic sharp burning taste), isobutanol (acetone/ nail varnish remover) and fatty acids, such as palmitic acid (soapy), isovaleric acid (strong pungent cheesy or sweaty smell), hexanoic acid (fatty, cheesy and waxy) and octanoic acid (rancid) which can turn your lovely peated spirit into a spirit which has the texture of lanolin and the aromas of sweaty socks and wet cardboard! As the feints can be around 40% of the charge, the still man will usually increase the pressure and it’s then just a case of running off the remaining spirit until the alcoholic strength has fallen to around 1% abv. Even with this increase in the rate of distillation it can still take 4-6 hours before the process has been completed. This speeding up of the distillation process is how some of the soluble fatty acids end up sticking to the inside of the still and lyne arm, and need to be adequately removed with a long, slow run of the following foreshots.

Finally heating the wort promotes what is known as a Maillard reaction, which is a form of nonenzymatic browning. It results from a chemical reaction between an amino acid and a reducing sugar. At low levels this can give a pleasant biscuity, malty, roasted coffee/ meat and nutty character (furfural) to the spirit but at higher concentrations can produce pungent cereal and sulphury notes, especially thiophenes and polysulphides. The use of copper can remove most of these unpleasant notes but if the still is pushed too hard, resulting in the spirit having minimal copper contact then it is possible to detect these sulphur notes in a spirit that hasn’t been aged in a sulphur tainted sherry cask! Thus, it is imperative that the distiller keeps an eye on the speed of the distillation process as rushing your distillation has a negative impact upon the character of the whisky.

So, there you have it. Distillation. It’s easy, isn’t it? The wort goes in there and the spirit comes out there! But like everything in life, it’s not as easy as that, as we have seen. Having spent a couple of days shadowing Neil MacTaggart, one of the stillmen at Bruichladdich I can tell you that a distiller’s day is taken up with monitoring, checking, filling in logs and generally tweaking valves and such like, as well as occasionally cleaning, eating, telling stories and reading the newspaper! Therefore, in my opinion, the stillmen like Neil are the unsung heroes of the whisky industry, because without their skill and devotion to this craft we would all be drinking rough old industrial spirit!